The Math Behind Rehab ROI

by Doug Davidoff | Nov 26, 2014 12:00:00 AM

The post originally appeared as commentary on Multifmaily Executive Magazine's website.

Rehabs present one of the most challenging pricing situations I’ve found in the apartment industry.

There’s a tug of war between the business desire to allocate capital in a way that provides a measurable real return on investment (ROI) and the human desire to preside over a nicer portfolio. Candidly, I find that a lack of familiarity and comfort with the math behind ROI calculations often gets in the way—and not always just from the jobsite side of the team.

The basic premise of rehabs* is straightforward: An operator invests $X to increase rent $Y, gaining a return of Z% in the process. As long as Z% is higher than the cost of capital, the overall return is positive.

Seems simple enough, right? But I’ve encountered several issues that cause me to believe that operators aren’t always getting what they think they’re getting from their rehab investments.

Renovations Aren’t Forever

I frequently hear something like this from rehabbers: “We’re putting $3,000 into a rehab and need a 10 percent ROI. So as long as we get a $25-a-month bump in rent, we’re good.”

Twenty-five dollars times 12 months is $300 a year, which is a 10 percent return on a $3,000 rehab cost. What’s wrong with that? Nothing—if you’re going to get the rent bump in perpetuity. But of course, we’re unlikely to get that—every upgrade has some life span to it, and that life span significantly affects the project’s actual ROI. In fact, there’s a good chance the units being considered for renovation have already been upgraded within the past five to 10 years.

In other words, renovations have a set amount of time during which they can be considered “fresh” before they need to be done again. This point is often overlooked, however, in evaluations of rehab plans, even though it can have a profound impact on the relationship between what’s spent on the rehab and the additional revenue the expenditure will earn.

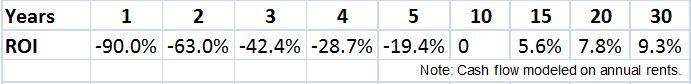

Just take a look at the numbers below to see the actual ROI, by life span, of the rehab in our $3,000 example:

These figures show that anything less than a 10-year life span yields a negative return. Meanwhile, it takes a 20-year life to yield just a 7.8 percent return, and even a 30-year life yields only a 9.3 percent return.

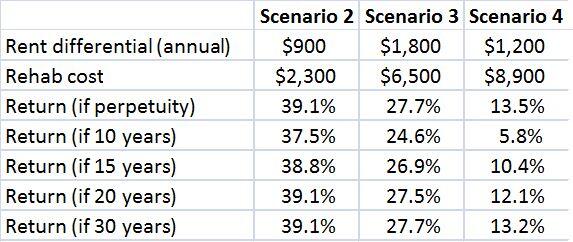

To bring this realization into a real-world context, below are several actual examples of calculated returns based on renovation numbers I’ve seen covered by the trade press.

As you can see, just like the owners in my original example, it’s highly unlikely the owners in Scenario 4 above are actually going to achieve anything near the returns they’re trumpeting. On the other hand, the operators in scenarios 2 and 3 are getting very good returns. Scenario 2, while not yielding big total dollars, is a home run in terms of rate of return.

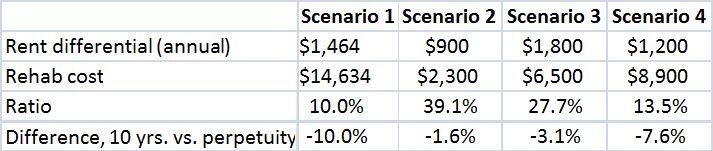

An important point to recognize is that the higher the ratio of rent gain to rehab cost, the less the life span affects the return. Since the initial investment is made back more quickly, a shorter life span generates a value closer to the “return in perpetuity” calculation:

Faulty Logic: Lowering the Base Rent to Protect ROI

Here’s a conversation that may be familiar to you. If it’s not, I guarantee it’s familiar to your pricing and revenue manager:

Community manager (CM): “I need to lower my one-bedroom prices.”

Pricing and revenue manager (PRM): “OK, what exactly makes you feel that way?”

CM: “I’ve got a few units that have been sitting vacant for too long.”

PRM: “That’s interesting. Anything those units share in common?”

CM (somewhat sheepishly): “Yeah, those are the units we’re doing the rehab on.”

PRM: “OK. Then we really need to reduce the upcharge for the renovation, not reduce the price on all units in that unit type.”

CM: “Oh, no. I can’t do that. Then I won’t be able to get the ROI on the rehab!”

A lot of rehabbers misguidedly evaluate their “return” based on the upcharge for the renovation. But if we reduce the base rent on all units in a unit type because the renovated units aren’t leasing, it’s a double whammy—we aren’t really getting the ROI on the renovation, and we’re actually now leaving money on the table for the unrenovated units.

The good news about the above dialogue is that the conversation actually occurred. There’s a hidden value destroyer any time overpriced renovations cause exposure in a unit type to rise with a resulting decline in rent for all units in that unit type (whether through automated or manual revenue management).

It’s not easy, but the only way to be sure of a renovation’s return is to put both the renovated and the unrenovated units on the market and compare the average days on market (DOM) for each. If the average DOMs are statistically equivalent, then we know the differential we’re getting is due to the renovation; if the average is lower or higher for the renovated units, we know we’re under- or overcharging what the market will bear and need to make the appropriate adjustment. If that adjustment causes us to fall below an ROI threshold, we should stop doing the renovations. That’s not an easy decision to make, but it’s the right decision.

The Perils of Hidden Costs

The foregoing discussion shows that we need to think beyond the pure direct costs of upgrades to the upgrades’ “hidden” costs. For example:

- What is the increased vacancy loss due to increased turn times to complete the renovations?

- What are the management overhead costs related to planning, managing, and inspecting the renovations?

- For large projects, what’s the cost of the disruption the renovation causes elsewhere on the property? For example, will we have to reduce rents on all or some of the unrenovated units to make up for the inconvenience new residents will have to deal with? Will we have to be less aggressive on renewals during the construction period?

I see many operators get caught up in the bigger, apparently more sexy upgrades—granite countertops, stainless appliances, wood flooring, and so on. These may be necessary with Class A product, but with Class B properties, they may not be. When you spend thousands of dollars, you really need some serious rent growth to get a decent ROI—can you get that for these high-end finishes when you’re talking B, or even B+, product?

Instead, consider some lower-cost upgrades that often have more bang for their buck because of how noticeable they are. Take entryways, for example. A relatively small area of ceramic can “announce” them dramatically and make that all-important good first impression.

Then there’s the old adage that kitchens and bathrooms are what really make the sale. So consider some relatively simple and low-cost options there:

- Backsplashes are right at eye level and may get noticed even before the flooring does. Most apartments have relatively short wall spaces, which makes backsplashes particularly low cost but high impact.

- Faucet and handle finishes are much less expensive than brand-new appliances and can really spruce up the look of the bath and kitchen.

- Something as simple as a curved shower bar makes for significantly improved resident comfort at very low cost.

The point with all the above is to test and measure your assumptions. Only then will you know what truly yields the best ROI on your rehab.

*For purposes of this article, the terms “renovations” and “rehabs” are used interchangeably and refer to a significant improvement in the physical features of a unit for the purpose of enhancing rent.

Donald M. Davidoff is the founder of D2 Demand Solutions, a technology consulting firm specializing in the multifamily housing industry. You can contact him at donald@d2demand.com.